The importance of data modeling in TypeScript

Take a deep dive into TypeScript to explore the importance of data modeling.

Written by

Fabien Bernard

Published on

March 28, 2023

Introduction

Hey folks! Today we will deep dive into TypeScript to demonstrate the importance of data modeling.

Quite often, I found myself having to come up with very fancy solutions for solving what I thought was a simple problem. Even if it’s good practice (and sometimes quite fun), most of the time, this is a sign that the data modeling can be improved!

Welcome to my journey of implementing a “strategy pattern” in TypeScript!

What’s this?! It’s a “computer science term” to describe that you need to choose a strategy on runtime. Still don’t get it? Let’s jump into an example to see what we are trying to solve here.

We need to build this Settings component, this component will take a question as input, and… this question can be 1 of 18 question types.

To make this a bit more challenging, every question type has its own set of settings.

This is where the “strategy pattern” comes in. Depending on the question type, at runtime, I will choose a different strategy/component to display. So if I pass a ContactInfoQuestion I will render ContactInfoSettings, if I pass a NumberQuestion I want NumberSettings, and so on.

Also, to help me implement all those {questionType}Settings components, I want to have the most precise type I can. For example, NumberSettings will take a NumberQuestion as props, so I only have the relevant information about in the context of NumberSettings.

Let’s Summarize

In code, this is what I want:

function Settings(props: { question: Question }) {

switch (question.type) {

case "contact":

return <SettingsContact question={question} />;

case "number":

return <SettingsNumber question={question} />;

}

}

function SettingContact(props: { question: ContactQuestion }) {

/* I just have the context of the question of type === `contact` */

}

function SettingNumber(props: { question: NumberQuestion }) {

/* I just have the context of the question of type === `number` */

}Easy, isn’t it? It depends! Here is where we must stop and think about our data modeling.

Indeed, the shape of Question will define everything here, between a hardcore TypeScript problem, with type guards, infer, ternaries and so on, or something smooth that works out of the box.

Without Discriminator

Let’s start with the naive approach without any discriminator. Don’t you know what a discriminator is? Perfect, we are not using them! (don’t worry, I will come back to it 😅)

Here is our first iteration of the type Question:

type Question =

| {

title: string;

required: boolean;

min?: number;

max?: number;

}

| {

title: string;

required: boolean;

format: string;

separator: string;

};This is how to start a painful journey with TypeScript, just because you don’t have any discriminator! Indeed, how do I know what is what? And if I don’t know, how does TypeScript know? I have no explicit value to know that our first option is QuestionNumber and our second is a QuestionDate

But, this is solvable with TypeScript, using type guards like this:

function isQuestionNumber(question: Question): question is QuestionNumber {

return "min" in question && "max" in question;

}My advice is if you have this from your backend team, talk to them and fix the problem at the source! Really, you don’t want to do this to yourself!

Now let’s add this famous “discriminator”, but for some reason, in a metadata object (you know, to “keep this clean”, and yes, I made this mistake before 😓)

type Question =

| {

title: string;

required: boolean;

min?: number;

max?: number;

metadata: {

type: "number";

};

}

| {

title: string;

required: boolean;

format: string;

separator: string;

metadata: {

type: "date";

};

};Please note that we are using string literals here (”date” and "number") and not string, this is really important! Thanks to this added string literal, we can “easily” narrow our type, we can discriminate!

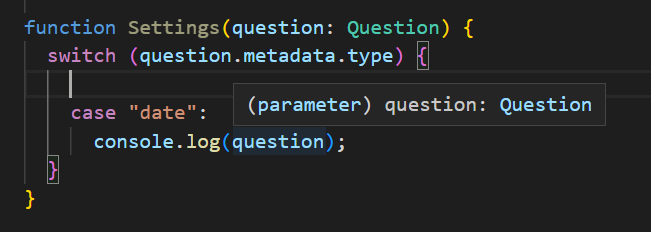

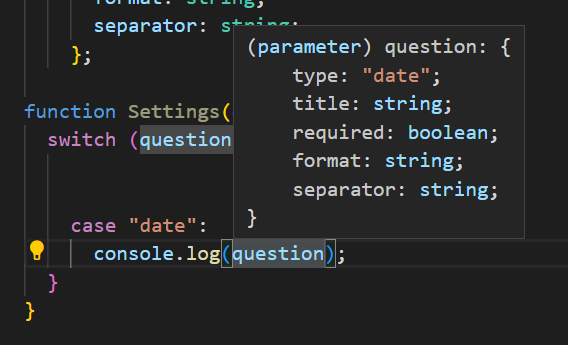

Let’s try!

Yes… I know… Disappointing… if you have this, out-of-box, TypeScript will still not help you, so there are two choices:

- Long party of writing type-guards → Boring and tedious

- Add a little

as QuestionDateand we are good to go → Error-prone and we are bypassing Typescript

This is usually when you start saying that TypeScript is stupid, and yes, in this case, you are right! And maybe, in future updates of TypeScript, this scenario will work!

Let’s Fix This

The fix is actually quite easy, we just need to move the type (our discriminator) to the top level:

type Question =

| {

type: "number";

title: string;

required: boolean;

min?: number;

max?: number;

}

| {

type: "date";

title: string;

required: boolean;

format: string;

separator: string;

};And voilà! Without any TypeScript guru skills required, you have exactly what you want!

Remember: If you want TypeScript to discriminate, the discriminator needs to be top-level!

Also, keep in mind that when you have a tough problem to solve with TypeScript, challenge the data modeling!

Component Part

Our switch statement is working, but what about our component prop?

To keep it simple, we can split our Question into multiple types

type NumberQuestion = {

type: "number";

title: string;

required: boolean;

min?: number;

max?: number;

};

type DateQuestion = {

type: "date";

title: string;

required: boolean;

format: string;

separator: string;

};

type Question = NumberQuestion | DateQuestion;Doing so, we can use NumberQuestion type as props in my component, which is simple and easy.

But wait! we can be smarter! So we don’t have to extract every union subtype (because, yes, we always realize this after writing everything in line 🙃). Let’s use a type helper 🪄

export type QuestionType = Question["type"];

export type QuestionOfType<T extends QuestionType, U = Question> = U extends {

type: T;

}

? U

: never;First, we extract the type from our union, QuestionType will be "number"|"date" in our reduce example. So every time we add a new question type in my union, this will follow.

Second, and this is where this is getting interesting, QuestionOfType<>!

We are using this QuestionType to constrain our generic. This gives us autocompletion later when we will use the helper and give guidance. T is our input, like a function parameter.

We also need a U , but we don’t want this as an entry, this is why we are giving the Question type as default. Also, you might ask why do we need a generic at all? This is to allow TypeScript to narrow the resulting type. Indeed, if I remove this U and write Question extends {type: T} ? Question : never This will always result in never since we are evaluating {type: T} on the entire Question instead of a shape.

Lastly, the logic:

If the type U extends { type: T }, returns U; otherwise, returns never . This is narrowing our union type to the subtype that extends { type: T } , basically discriminating on type !

Let’s try to use this new helper in our component

export default function SettingsDate(props: {

question: QuestionOfType<"date">;

}) {}Both approaches are totally valid. But the second one brings us something interesting, and we can use the question.type as generic.

In my context, my Settings<type> component needs two more things: formId and questionId and this is where we can utilize this generic to create a standard SettingsProps

export type SettingsProps<T extends QuestionType> = {

question: QuestionOfType<T>;

questionId: string;

formId: string;

};I now have a simple and robust way to share props across all our components

export default function SettingsDate({

questionId,

formId,

question,

}: SettingsProps<"date">) {}How beautiful is this? 😍 No guessing, no type assertion, and this without writing (and maintaining) 18 type guards!

I hope you did learn something today! If not, thanks for following my journey 😀 All the examples in this article are taken from XataForm, my in-progress project that should soon be open-source.

If you have any questions, suggestions, remarks, or just want to say hi, I’m always around in our Discord channel! (@fabien0102)